The Special Habitats of Wales - Sand Dunes

(Sand dunes at Dyfi NNR - picture courtesy Mike Alexander NRW)

The coasts of both North and South Wales are well known for their wonderful sandy beaches, making them popular holiday destinations for visitors from the UK and many other parts of the world. Behind many of these beaches are sand dune systems which provide homes for diverse forms of wildlife including plants and insects, some so highly specialised that without these dune habitats, they might well be driven to the point of extinction.

Many of our sand dune systems are covered by both UK and international legislation in order to protect their habitats and the species that depend upon them. Despite these designations there is an increasing recognition that all is not well with our sand dunes. Many species could soon become extinct unless we undertake important work to reverse some of the results of earlier interventions, undertaken in good faith, that have damaged the habitats and contributed to a decline of the wildlife species that live within them.

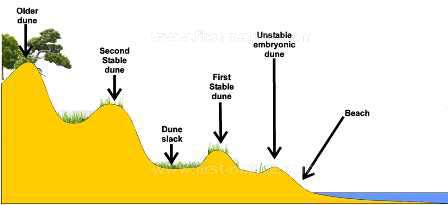

How sand dunes develop and mature - picture from Fascinated by Fungi by Pat O'Reilly

Left to their own and the weather's devices, sand dunes are dynamic systems. New dunes are formed by sand being blown in from the shore at low tide, and the sand on the dunes behind these embryonic dunes is also continuously moved and re-shaped by the wind. In recent years it was thought desirable that our sand dunes should be stablised, making them a less unpredictable force; that is because unstable dune systems can swallow up boardwalks, tracks, roads and even buildings in a remarkably short period of time during stormy weather conditions. As a result the proportion of mobile dunes in our sand dune systems has decreased, according to Countryside Council for Wales reports, from about 70% just 60 years ago to just 6% or so today. Bare sand habitats now form a mere 1.7% of the total area of Wales's sand dunes.

The rare Fen Orchid (Liparis loeselii) is one of the species being pushed towards extinction by over-vegetated dunes

The stabilisation of the dunes was brought about by a number of factors. Coastal developments such as residential homes, holiday parks and sea defences are thought to have had a considerable impact, as also did the deliberate introduction of specialist stabilising plants - Marram Grass for instance -which quickly establishes itself and puts down long and powerful roots. Once Marram Grass takes hold and the dunes become immobile, it is not long before other plants are also able to colonise these areas so that species that can survive only in the mobile dunes are soon crowded out by competition from these newcomers. In time the decaying matter from the new plants affects the purity of the sand, which eventually comes to more closely resemble soil; this in turn, encourages the growth of even more rank plants and shrubs.

In the case of Newborough Warren on the island of Anglesey in North Wales, the colonisation by Marram Grass in the area was so successful that the nearby villagers made a living from harvesting it for use in what became a thriving weaving industry.

Below: Dunes sculpted by the wind at Morfa Harlech NNR

What people had failed to understand was the vital importance of these mobile sand habitats on many rare species that cannot exist in the more stable and overgrown dunes.

We can begin to get an idea of the importance of Wales's sand dune habitats by considering the high level of conservation designations. Of the 56 dune systems in Wales occupying some 8000 hectares, 31 are SSSIs, 6 are SACs and 9 are National Nature Reserves (Merthyr Mawr, Kenfig, Oxwich, Whiteford Burrows, Stackpole, Ynyslas, Morfa Dyffryn, Morfa Harlech and Newborough Warren). These dune systems support numerous species that are entirely dependent upon the pioneering habitats created by shifting sand: 439 vascular plants, 171 bryophytes, 66 lichens, 289 fungi and 500 (at least) invertebrate species.

What can we do about it?

Tried and tested management techniques for rejuvenating sand dunes include so-called 'beach nourishment' (bringing in sand from other beaches and dumping or pumping it where required), grazing and scrub control, deep ploughing, and the stripping of vegetated turf to expose the sand below. More dramatic interventions which are being employed increasingly both in Wales and on mainland Europe (in Holland in particular) include the reactivation by mechanical means of 'blowouts' - dish-shaped hollows that can be naturally created when winds are strong enough to wrench plants out of the dunes and so mobilise the sand. Using diggers and trucks to remove overgrown turf to expose bare sand has proven to be very successful in Holland, and now a similar scheme is being carried out at Kenfig National Nature Reserve where the dunes have become so overgrown with scrub that they threaten the survival of rare species, notable among which is the Fen Orchid (Liparis loeselii). If successful it is hoped that this same method can be employed in other dune systems around the coast of Wales that also support rare and specialised plants, insects and animals.

Below: The Green Tiger Beetle lives in our sand dunes and needs bare sand for its survival. Picture: Mike McCabe NRW

Kenfig National Nature Reserve in Wales is the final frontier for the Fen Orchid, which has all but disappeared from many of its other sites in the UK - predominantly in the fens of East Anglia. It was known from 8 coastal sites in Wales but has now been lost from 7 of them. The number of plants recorded at Kenfig has declined steadily from around 10,000 in the early 1980s to a mere 159 in 2010. At Kenfig this little orchid grows in the dune slacks - flat areas in between sand dunes which are submerged in rain water during the winter and remain moist throughout the year. Although there are plenty of suitable dune slacks at Kenfig NNR, they are becoming too overgrown with plants that are in competition with the Fen Orchid.

Another factor necessary for this orchid's life strategy is now missing at Kenfig: newly formed dunes and dune slacks. The Fen Orchid is a pioneer, thriving on disturbance, and it can quickly colonise new slacks. The only completely new colonies of Fen Orchids are found in newly formed dune slacks, and it seems that the areas of bare sand found there are a crucial factor for the success of new plants.

The Fen Orchid is probably the best known of the species threatened by the lack of pioneer habitats in our sand dune systems, but there are plenty of others that are similarly endangered; the proposed intervention programme in some of our sand dune systems is a matter of life or death for many of them. The aim is to restore a balance in our sand dune systems so that there will be a minimum of 10% bare sand and at least 30% pioneer habitats.

Below: The male Green Tiger Beetle uses its jaws to hold on to his mate during the mating process. Picture Mike McCabe NRW.

One of the quirky creatures that inhabit our sand dunes is the Green Tiger Beetle (Cicindela campestris). As another species that prefers bare ground, it will certainly benefit from the rejuvenation of the dunes to provide more bare sandy places in which it can live and hunt. This bright iridescent green coloured beetle is a fearsome and agile predator with long legs as well as strong jaws with several teeth; it can move at remarkable speed on the ground to catch its prey - caterpillars, ants and any other small invertebrates within range. This beetle prefers not to fly and will only take off if disturbed, and even then it flies only a short distance - again at great speed.

Green Tiger Beetles breed in summer and lay their eggs separately in tiny burrows. When they hatch, the larvae remain in the burrow during the first winter of their lives; there they lie in wait for unsuspecting insects to fall into their lairs. The larvae grab their prey with jaws every bit as ferocious as those of the adult beetles. As they grow the larvae need to enlarge their burrows to accommodate their increasing size, moulting their skins three times during the process.

Below: A Green Tiger Beetle larva in its 'burrow'. Picture Mike McCabe NRW.

Look out for these fascinating little creatures in the bare sandy parts of our dune systems. Bare ground warms up quickly, and the warmer the Green Tiger Beetle is the better it is at racing to catch its food. If you pick one of these little gems of beetles up to inspect it more closely you may well find out how effective its jaws are: it can give you quite a powerful 'nip' - you have been warned!

The Best Sand Dune Nature Reserves in Wales include:

Merthyr Mawr NNR

Kenfig NNR

Oxwich NNR

Whiteford Burrows NNR

Stackpole NNR

Dyfi NNR (Ynys Las dunes)

Morfa Dyffryn NNR

Morfa Harlech

Newborough Warren NNR