Casting Techniques

Trout Casting - Sea Trout Casting - Salmon Casting

In all efficient casts it is the rod that does the work, and so you really do need to understand how flexible your chosen fly rod is in order to enable the rod to cast the line. As a general rule the more flexible a rod is (this is referred to as a slow action rod) the more slowly you need to move, and the stiffer the rod is (a fast or tip action rod) the faster you can move. Beginners tend to move too quickly with jerky movements, and so a faster action rod creates fewer problems and tangles while you are getting to grips with basic casting techniques. Try to use the same rod while you are learning the basic casting techniques. Once they are mastered you will find it easier to adjust the timing of your casting to different rods if you are going to use more than one rod for different types of flyfishing - salmon or sea trout fishing for instance.

Gentle and accurate casting is an essential skill for successful flyfishing, and so it is really worth the time and effort involved in learning properly. Brute force is no substitute for casting skill and is a great recipe for breaking a rod, so if you feel frustrated stop and take a break for a while.

Casting for Trout and Grayling

Don't grip the rod handle too tightly; hold it gently and place your thumb on the top of the handle. Not only is this the most comfortable grip for casting, but having your thumb on the top of the rod handle also means that you can quickly check the angle of the rod when it is above you. If your thumb is vertical so is the rod, if your thumb is angled back so is the rod, and so on. As the fly line always follows the rod tip, by simply checking the angle of your thumb on the rod you will be able to see immediately if you are casting the loine (and hence the fly) down behind you.

When describing the position of the rod during casting, instructors commonly refer to an imaginary clock face where 12 o’clock is directly above your head, 9 o’clock is directly in front of you etc. Although this is helpful to some people, imagining casting around a clockface can cause the tip of the rod to move in a circular movement and this will often lead to casting too low behind you on the back cast. A better method - one that properly mimics the movement of an effective back cast - is to imagine picking up a telephone from a desk in front of you and raising it to your right ear (if you are right handed). This ensures that you lift the rod straight up (rather than in a circular movement) and that the rod handle is positioned level with your ear, which is the best way to ensure that it is vertical at the top of the back cast.

Whichever method you choose remember that at the top of a basic overhead cast the rod should be as close to vertical as possible. This fundamental rule only changes if you are fishing in very windy conditions, and this is dealt with in more detail in the description of the basic overhead cast, which is covered below.

The overhead cast

This is a means of casting a fly on to the water whereby the fly line first moves back and forth above your head.

Flexing of the wrist should be kept to an absolute minimum in all parts of this cast.

- Face the target, standing in a relaxed manner with the rod handle resting against the under side of your wrist and forearm, and with your thumb on the top of the rod handle. Prevent extra line running off the reel by holding the fly line still in the left hand (if you are right handed) which should be approximately level with the waist. Alternatively trap the line against the rod butt using the index finger of your casting hand.

- Start with the rod tip pointing at the line in the water.

- Raise the rod slowly to the 10 o’clock position and increase speed up to the vertical position (your thumb should be level with your ear, and the rod handle should be vertical and lying almost against the wrist).

- Pause and allow the line to straighten out high overhead and behind.

- ‘Tap’ gently forward to 10 o’clock, sending the line forward across the water.

- Lower the rod towards the surface of the water as the line settles.

Using the overhead cast in windy conditions

If a breeze is blowing from right to left, adjust the position of your right hand so that the line passes over your left shoulder during the back and forward cast.

If the breeze is coming from the front, lean slightly forward into the breeze so that on the back cast you can stop as normal on the back cast but with the rod slightly angled forward instead of vertical. On the forward cast tap the line down to the 9 o’clock position.

If the breeze is coming from behind, lean backward into the breeze so that the back cast goes slightly further back (to the 2 o’clock position) and end the forward cast at the 11 o’clock position.

How to shoot line on the overhead cast

This is a useful method of casting further without the need for a lot of 'false casting'

At the 10 o’clock position on the forward part of overhead cast, release all extra fly line held in left hand and allow it to shoot out. This cast requires a strong ‘forward tap’ followed by a slight pause as the line shoots across the water.

Tightening the loop

So-called tightening the loop refers to a technique used on the forward part of the overhead cast. The loop refers to the U-shaped profile of the fly line as it travels out across the water in front of you - the narrower the U-shape is the more effective it will be when casting into tight lies underneath or between branches of trees, or when casting into a head-wind. How wide the U-shaped loop is on the forward cast is determined by one thing only, how far you drive the rod down on the intial tap of the forward cast. Lowering the casting arm too far forward means that the line will travel across the water in a wide arc which is aerodynamically inefficient and very difficult to control when targeting a fish in a confined space. By gently moving the rod forward and stopping it very high after the initial tap (at 11 o'clock) the loop will become much tighter and, therefore, more effective in windy conditions and when targetting fish.

False casting

False casting is a repetition of the the movements of the Overhead cast - the back and forward casts - without allowing the line to settle on the water at the end of each forward cast. It should be a gentle and rhythmic movement of the line back and forth overhead and performs two functions. Firstly, it enables you to target a fish both in terms of its distance from where you are casting and its position, without repeated splashy landings of the line on the water whilst you try to get enough line out to cover the fish. Secondly it enables you to gradually extend the amount of line you are casting by releasing it bit by bit on the forward false cast before finally allowing the line to land on the water. This is particularly useful if you have 'retrieved' a lot of line during fishing and need to cast it out again to reach a particular target.

Although false casting can be a very useful technique its use should be kept to a minimum because on bright sunny days fish can often spot the line passing back and forth over them, and also see light flashing on the rod as you move it back and forth. Extending too much line can easily 'overload' the rod causing the line to drop too far behind you on the back cast and then lose momentum on the forward cast.

The side cast

This cast is almost identical to the overhead cast and is useful if you are fishing in a place that prevents you from casting the line directly above and behind you due to the presence of a high, or tree-line river bank. Instead, it enables you to make use of the river corridor to cast and lengthen the line before making the final cast. The rod should move in a horizontal plane from the right to the left (if right handed) directly in front of you rather than overhead, with a slight upward lift on the right hand cast to avoid catching bankside vegetation. Although accuracy is slightly more difficult with this cast it is an excellent way of casting to a fish which is lying beneath overhanging branches on either side of the river.

The roll cast

The roll cast is a way of casting out line without the need for a back cast. It contains some of the elements of the basic overhead cast, such as the initial lift to 10 o’clock on the back cast as well as the final follow through (lowering the rod to the water as the line settles). Here are three examples when the roll cast works really well:

When there are obstructions behind – trees, bushes etc

To straighten a tangled heap of line prior to making an overhead cast

To bring a sunk line to the surface of the water before making an overhead cast

For the roll cast, the stance is as for the basic overhead cast. There are three movements to the roll cast - a lift, a sweep and a tap forward.

The lift. Start with the rod tip pointing at the line in the water. Raise the rod directly in front of you to the 10 o’clock position, and then PAUSE while the line settles.

The sweep. Sweep the rod around to your right-hand side (if you are right handed), then smoothly back in a wide arc and then up until the thumb is level with your right ear. The rod should now be angled out to the right and slightly behind you so that the line and rod form a letter D, the rod being the straight part of the D and the line forming the belly. Again PAUSE while the line settles beside you.

Raise the rod slightly and ‘tap’ forward to the 10 o’clock position allowing the line to roll out above the water in front of you. This movement is akin to hammering a nail into a wall directly in front of you at eye level.

Using the roll cast in windy conditions

With a breeze coming from the front, drive the rod a little lower on the forward cast.

If the breeze is from right to left, roll cast over your left shoulder (or use your left hand).

The single haul

The single haul is based on the overhead cast and includes shooting line on the forward part of the cast. In this cast, the line hand (the non-casting hand) pulls down or hauls on the line during the lift and releases it at the 10 o’clock position on the forward cast.

The stance and grip on the rod are as for the overhead cast. At the beginning of the cast the line hand grips the line close to the butt ring of the rod. Throughout the single haul your rod arm moves in exactly the same sequence as for the overhead cast, and it is most important to move the forearm rather than merely flexing the wrist.

The haul. As the rod reaches the acceleration point at 10 o’clock, start to haul down with your line hand, pulling line back through the rod rings. Your line hand should reach maximum ‘pull down’ as the rod reaches the vertical position.

The release. Tap forwards as in the overhead cast, releasing the line at the 10 o’clock position on the forward cast.

Advanced Trout Casting

Double haul

The double haul is also based on the overhead cast. It is a means of casting greater distances and it can also help to improve accuracy in windy conditions. The first haul is made on the back cast; a second haul is made on the forward cast, and the line is released after the ‘tap’ forward. The key to the double haul lies in the movements of the line hand: if the hauls are applied at the right moment, rod loading, line speed and therefore distance can be dramatically increased.

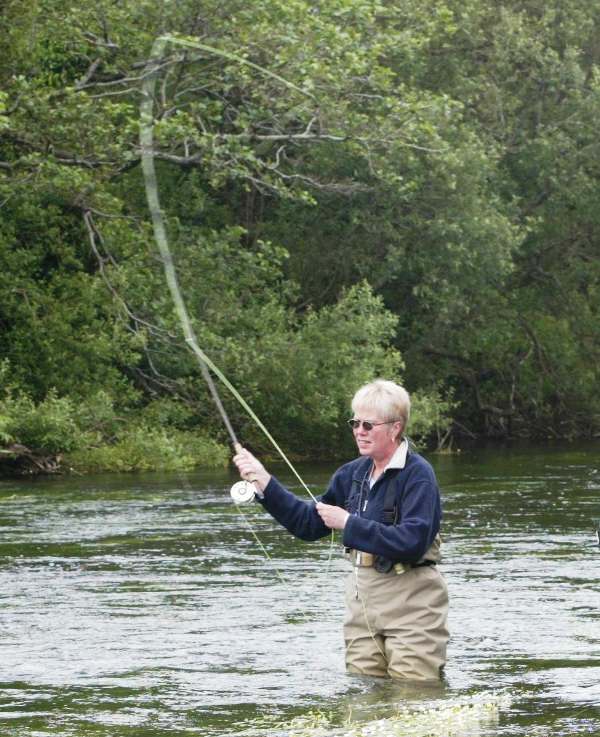

The picture below shows a ‘haul’ in progress during the forward cast.

The double haul begins in exactly the same way as the single haul, but your line hand must return the line hauled on the back cast at the 1 o’clock position. Do this by keeping hold of the line while lifting your hand back up to the butt ring of the rod, which is now level with your ear as in the basic overhead cast.

The second haul is made by pulling sharply but smoothly downwards with your line hand at the beginning of the forward cast. After tapping the rod forward, let go of the line when the rod reaches the 10 o’clock position.

It is most important to synchronise the downward haul of the forward cast with the acceleration of the rod. Only when the two movements are made simultaneously will you obtain the extra power that this cast can provide.

One final point … just as it is possible to create leader tangles if you snatch the rod forward jerkily, so it is also common, at least when first learning the double haul, to get tangles because the haul with the line hand is jerky. With practice, however, you should be able to make smooth accelerating movements with both the rod hand and the line hand, so resulting in tangle-free, accurate and delicate presentation even at great distance.

The 'Wiggle' cast

Success in dry-fly fishing for trout is dependent on many things, but one of the most important is that the fly should behave as much like a natural insect as possible once it lands on the water. Conflicting currents which lie between you and the fish are one of the main causes of the fly 'skating' or moving unnaturally because they push and pull the line around. The ability to add some slack into the line which will absorb some of the effects of the conflicting currents can buy some vital extra seconds of the fly behaving normally whilst it is visible to the fish. The way to achieve this is to very gently 'shake' the rod from side to side just before the line lands on the water on the forward cast. The movement creates wiggles in the line which act as a shock absorber and allows the fly to move naturally when landing close to a targetted fish even in quite turbulent water.

Casting a 'mend'

So-called mending the line is another method frequently used to buy fishing time by slowing down the speed at which the line is manipulated by the water. Most flyfishers make a cast followed by an exaggerated movement, once the line is on the water, either to the right or left to creat a 'loop' in the line which slows down the impact of the current. The problem with this method is that it often wrenches the fly away from the lie of the trout before it has had a chance to see it. A far better method is to cast a mend 'in the air' before the line lands on the water. This can be achieved by moving the rod either to the right and left, or left and right (depending on whether you want to create the loop upstream or downstream) on the forward cast just before the line lands on the water.

Casting for Sea Trout

Of all of the four species that we flyfish for it is Sea Trout that is the most difficult and causes the most frustration. Firstly, there is the not inconsiderable hurdle that, in the UK at least, we fish for Sea Trout at night, and the second problem is, that in all but really low water conditions, it is necessary to fish with tackle setups which are heavy enough to get flies down to where the Sea Trout lie which is often at the bottom of deep pools.

We generally fish for Sea Trout with single handed rods, and a mid-to-tip action 9ft 6in #7 rod would be a good choice. Some prefer to fish with 10ft #9 or #10 rods but casting a heavy rod all night can be a pretty tiring experience. There is more about fishing setups on our dedicated Sea Trout Fishing page.

If you are lucky enough to fishing on a river where you can make a back cast without the hindrance of trees or high banks it will be possible to use the overhead cast, and this is ideal for most tackle setups. Long and very accurate casts are often needed for Sea Trout fishing because the fish will nearly always be lying under the far bank of the river. The first thing you will notice about casting in near pitch darkness is how difficult it is to judge distances accurately - the far bank will appear much closer to you than it really is because your vision is affected by shadows of overhanging vegetation on the water. The second problem is that, without seeing your fly line passing back and forth across the river the timing of your casting becomes disrupted and confused. Only time and practice can solve this problem. Don't be too ambitious with distance to begin with, just get used to casting in the dark before trying to cast long distances - tangles are night are much worse than tangles by day! A smooth and gentle casting action is essential: any jerks and sharp movements will result in tangles, especially if you are casting a team of two or three flies.

The ability to spey cast with a single handed fly rod offers a great advantage for salmon and sea trout fishers since the fly and line never pass behind you and are, therefore, kept well out of the range of bankside vegetation and overhanging trees. It is possible to perform all of the spey casts with a single handed rod.

Spey Casting with a single handed fly rod

All spey casts are based on the Roll Cast. If fishing in a very confined space the roll cast can often be the only option. If you are on the right hand bank of the river (see note below) your right hand should be uppermost on the rod when executing a roll cast. The reverse is true of fishing from the left hand bank. Spey casts have several advantages over the basic overhead cast and the roll cast. In particular they are feasible in places where there is no room for a conventional back cast, more effective when you need to make a wide angle change of direction, and safer, because the fly is always downwind of and never behind you; this avoids the risk of being hit from behind or the side by a heavy fly on the forward cast.

Single Spey Cast - use this cast in an upstream breeze

When fishing from the left bank (which bank am I on?), hold the rod in your right hand. There are three stages in this cast are the lift, the sweep, and the hit...

The lift

1. Stand facing the target but leave the rod tip pointing downstream towards the fished out line, with the rod tip down at the water.

2. Raise the rod slightly towards the near bank and, by bending your upper arm at the elbow, to about the 10 o’clock position. Pause briefly…

The sweep

3. With your right hand sweep away, out and round an imaginary plate sitting on your right shoulder until your right thumb comes around to the right side of your shoulder and up to a position level with your right ear. This movement should have swept the line and the fly upstream so that the last metre ( about three feet) of line and the leader touch down approximately 1.5 rod lengths away and upstream of you with a D loop formed behind the rod, which should now be facing the target. Pause briefly to allow the line to land on the water…

The hit

4. Punch the rod forward, stopping sharply at the 10 o’clock position in front of you to launch the loop of line out across and above the water. This is a wrist and forearm movement not a shoulder movement. Gently lower your right arm as the line settles on the water.

Double Spey Cast - use this cast in a downstream breeze

This is essentially a single spey cast with one extra movement. It is not a great distance cast unless assisted by a strong downstream breeze. When fishing from the left bank, hold the rod with your left hand; when on the right bank, use your right hand. The double spey cast is described below for fishing from the right bank of a river; simply swap hands for a description of casting from the left bank.

1. Face the target, holding the rod in your right hand leaving the rod tip pointing at the fished out line downstream.

2. Lift the rod just slightly and tow the rod and line upstream until your right arm is across your body and the rod tip is pointing upstream. This will bring enough line upstream to form the loop during the sweep stage of the cast, but the fly will still be downstream of you.

The lift

3. Just as you did for the single spey, lift the rod to the 10 o’clock position and slightly in towards the nearside bank upstream. Pause briefly...

The sweep

4. As in the single spey, sweep the rod tip out and around (back downstream) to end up with your right thumb level with your right ear. As you do so the line will peel back and round to form a D loop behind the rod just off your downstream shoulder with the fly, the leader and the bottom of the loop anchored in the water. Pause briefly...

The hit

5. Drive the loop out across the river as in the single spey cast.

Snake Roll - use this cast only in a downstream breeze

Like the double spey cast, for which it is a more powerful alternative casting technique, the snake roll must be used only in a downstream wind. The snake roll can be used to create very deep loops that load the rod fully on the back sweep; as a result, for distance casting the snake roll is much more efficient than the double spey cast.

This description is for casting from the left-hand bank of a river. Simply swap hands for a description of casting from the right-hand bank.

- Begin as for the double spey cast, holding the rod in your left hand.

- Lift the rod in towards the bank (downstream of you) and then curve the rod tip up and out towards the river before tucking back under (as if describing a large letter e) before lifting back up to the launch position with your thumb level with your left ear. This movement should lift the entire line off the water and bring it spiraling back towards you, placing the required last few feet of line onto the surface about a rod’s length downstream of your left shoulder. At the same time a D loop will form behind the rod.

Note that when you are casting from the right-hand bank the 'e' will be reversed (as you see it) as though you are looking at its reflection in a mirror.

- Drive the loop out across the river as in the single spey cast.

Casting with sinking lines

When you know that Sea Trout are in the river, probably the most common cause of failure to catch fish is not fishing deep enough. One it is completely dark it may be necessary to change to a heavier tackle set up in order to get your flies down deep enough for the Sea Trout to see them.

When using a sinking line for Sea Trout fishing, it is advisable first to roll cast to bring the line up to the surface prior to recasting across the river using an overhead cast. Spey casting a single handed rod with a heavy line and flies is extremely difficult and so if the use of heavy tackle is called for and bankside vegetation means that you are unable to overhead cast it is a good idea to change to a smallish double handed rod - say 12 - 13ft. This will make lighter work of spey casting a sunk line and heavy flies.

A critically important factor when casting a sinking line is to keep the line moving once you have brought it up to the surface. Do not pause after the preparatory roll cast or the line will immediately sink below the surface again making an effective spey cast virtually impossible.

Mending the Line

Mending the line when fishing for Sea Trout is seldom a good idea. It is essential that your casts should reach the far bank of the river where the fish are lying. Having achieved that (difficult enough in itself, especially in pitch darkness!), mending the line which immediately wrenches the fly away from the Sea Trouts' lies under the far bank before they have had time to sink to the right depth is a complete waste of time. If you believe that mending the line is required it is far better to spend some time (during the day0 learning the 'air mend' technique described below.

Shown on the left is the the casting technique for casting an 'air mend'. With practice you can create an upstream mend by means of a gentle side-to-side movement of the rod while the line is still travelling through the air. This is particularly useful when fishing with fast-sinking lines, which are very difficult to mend once they have touched down onto the surface of the river.

Casting for Salmon

It is possible to overhead cast from the bank with a double-handed rod as well as a single-handed rod, and while the technique can achieve impressive distances it can be very dangerous in windy conditions. It is impracticable to us this technique if you are fishing on a river lined with high banks or trees. If you intend to make an overhead cast with a double-handed rod and you are on the right-hand bank of the river (see note below), your right-hand should be uppermost on the rod handle. The reverse is the case, of course, if you are fishing from the left-hand bank of the river.

Spey casting with a double-handed rod is by far the safest and most effective technique when fishing for salmon because it enables you to fish anywhere, and to fish in even the windiest of conditions since the casts themselves are designed to make use of the wind.

Spey Casts

All spey casts are based on the Roll Cast.

If fishing in a very confined space the roll cast can often be the only option. If you are on the right hand bank of the river (see note below) your right hand should be uppermost on the rod when executing a roll cast. The reverse is true of fishing from the left hand bank.

Although based upon the roll cast, just as with a single-handed rod spey casts with a double-hander have several advantages over the basic overhead cast and the roll cast. In particular, a spey cast is:

- Feasible in places where there is no room for a conventional back cast

- More effective when you need to make a wide angle change of direction

- Safer, because the fly is always downwind of and never behind you; this avoids the risk of being hit from behind or the side by a heavy fly on the forward cast.

Which bank of the river am I on or nearest to?

When you are standing in the river margin and facing downstream, the river bank is given the name of whichever of your shoulders - left or right - is closest to the bank. In this picture, the river is flowing from the left to the right and the photograph has, therefore, been taken from the right-hand bank of the river.

Single-handed or double-handed rod?

Many of the finest salmon rivers are wide, deep and fast flowing. Using a double-handed rod enables you to cast farther than is possible with a single-handed rod; it also allows you to hold more of the fly line up above the surface, slowing down the rate that your fly moves across the river so that a salmon is more likely to see and move to it. Spey casting is also useful on smaller salmon rivers, where a single-handed rod may be more appropriate. Sea trout fishers also benefit from acquiring Spey-casting skills, because they do not have to worry about hooking trees behind them when fishing at night. Powerful double-handed rods also make light work of casting heavy flies and lines.

Which Spey Cast?

Here Pat O'Reilly begins a single spey cast from the left hand bank of the Deveron.

The decision on which spey cast to use depends solely on wind direction. A single spey is used when the wind is blowing upstream, so that an arc of line, together with the leader and the fly, are swept upstream before hitting out to the target.

The double spey is used in a downstream wind, so that an arc of line, together with the leader and the fly, are swept downstream before hitting out towards the target.

If there is little or no wind, or a wind blowing directly across the river, then either spey cast can be used (and you can alternate between single and double spey in order to practise both). Although it is the wind direction that determines which spey cast should be used, it is the bank that you are fishing from that determines which hand is uppermost on the rod.

Right hand or left uppermost on the rod?

Which hand should be uppermost on the rod when making a spey cast or a snake roll cast? Well, it all depends on which bank you are fishing from. You will remember that the choice of casting technique is determined by wind direction, and is fundamentally a safety consideration. Once you have that clear, there is only one way of holding the rod that will actually work. (If you have the wrong hand uppermost on the rod you will end up casting away from the river rather than across it!)

For those who find it helpful to memorise sets of rules, the table below answers the question ‘Which hand should be uppermost on the rod?’ for various wind and water directions and for each of the three so-called continuous-motion casting techniques of single and double spey and snake roll described in this section.

Casting technique |

Wind direction |

Riverbank you are on or nearest to |

||

Upstream |

Downstream |

Right |

Left |

|

Single Spey |

Yes |

No |

Left hand up |

Right hand up |

Double Spey |

No |

Yes |

Right hand up |

Left hand up |

Snake Roll |

No |

Yes |

Right hand up |

Left hand up |

What about single-handed rods for salmon or sea trout?

These descriptions of spey casting apply when using a double-handed rod; however, where the text says ‘right hand uppermost’ simply read it as ‘rod in the right hand’ and you have a description of spey-casting with a single-handed rod.

Below: Sue Parker making a single spey cast with a single-handed rod held in the right hand while fishing from the left-hand bank.

Single Spey Cast - use this cast in an upstream breeze

When fishing from the left bank, your right hand should be uppermost on the rod; when on the right bank your left hand needs to be uppermost. The three stages of this cast are the lift, the sweep, and the hit...

The lift

1. Stand facing the target but leave the rod tip pointing downstream towards the fished out line, with the rod tip down at the water. Your hands will be crossed at this point.

2. Raise the rod slightly towards the near bank and, by bending your upper arm at the elbow, to about the 10 o’clock position. Pause briefly…

The sweep

In this picture ou can see the line being swept around from its fished-out position on the left to the right hand side of the angler.

3. Turn right with your upper hand and sweep away, out and round an imaginary plate sitting on your right shoulder until your right thumb comes around to the right side of your shoulder and up to a position level with your right ear. This movement should have swept the line and the fly upstream so that the last metre ( about three feet) of line and the leader touch down approximately 1.5 rod lengths away and upstream of you with a D loop formed behind the rod, which should now be facing the target. Pause briefly to allow the line to land on the water…

The hit

4. Punch the rod forward, stopping sharply at the 10 o’clock position in front of you to launch the loop of line out across and above the water. This is a wrist and forearm scissors movement made with both hands to flex the rod; it is not a shoulder movement.

Double Spey Cast - use this cast in a downstream breeze

This is essentially a single spey cast with one extra movement. It is not a great distance cast unless assisted by a strong downstream breeze. When fishing from the left bank, your left hand should be uppermost on the rod; when on the right bank, your right hand needs to be uppermost. The double spey cast is described below for fishing from the right bank of a river; simply swap hands for a description of casting from the left bank.

1. Face the target but leave the rod tip pointing at the fished out line downstream, with the rod positioned across your stomach and your right hand uppermost on the rod. At this stage your hands will not be crossed as they were for the single spey cast.

2. Lift the rod just slightly and tow the rod and line upstream until your hands are crossed. This will bring enough line upstream to form the loop during the sweep stage of the cast, but the fly will still be downstream of you.

Below: Sue Parker tows the rod and line upstream in preparation for executing a double spey cast from the left hand bank.

The lift.

3. Just as you did for the single spey, lift the rod to the 10 o’clock position and slightly in towards the nearside bank upstream. Pause briefly...

The sweep

4. As in the single spey, sweep the rod tip out and around (back downstream) to end up with your right thumb level with your right ear. As you do so the line will peel back and round to form a D loop behind the rod just off your downstream shoulder with the fly, the leader and the bottom of the loop anchored in the water. Pause briefly...

The hit

5. Drive the loop out across the river as in the single spey cast. Snake roll. (Use this cast only in a downstream breeze.) Like the double spey cast, for which it is a more powerful alternative casting technique, the snake roll must be used only in a downstream wind.

Snake Roll - use this cast only in a downstream breeze

On the right, the snake roll cast being executed from the left hand bank of the river.

Like the double spey cast, for which it is a more powerful alternative casting technique, the snake roll must be used only in a downstream wind. The snake roll can be used to create very deep loops that load the rod fully on the back sweep; as a result, for distance casting the snake roll is much more efficient than the double spey cast.

This description is for casting from the left-hand bank of a river. Simply swap hands for a description of casting from the right-hand bank.

- Begin as for the double spey cast, facing the target and with the left hand uppermost on the rod.

- Lift the rod in towards the bank (downstream of you) and then curve the rod tip up and out towards the river before tucking back under (as if describing a large letter e) before lifting back up to the launch position with your thumb level with your left ear. This movement should lift the entire line off the water and bring it spiralling back towards you, placing the required last few feet of line onto the surface about a rod’s length downstream of your left shoulder. At the same time a D loop will form behind the rod.

Note that when you are casting from the right-hand bank the 'e' will be reversed (as you see it) as though you are looking at its reflection in a mirror.

- Drive the loop out across the river as in the single spey cast.

Casting with sinking lines

When salmon are running, probably the most common cause of failure to catch fish is not fishing deep enough. Once you have mastered the art of casting a sinking line, you have the flexibility to present flies of an appropriate size at whatever depth you wish.

When using a sinking line, it is advisable first to roll cast to bring the line up to the surface prior to using a single spey cast; this will avoid the risk of overloading the rod and perhaps breaking its top section. In the case of the double spey cast, the action of towing the rod upstream is often enough to bring the line up to the surface ready to make the cast, and so a preparatory roll cast is not always necessary.

A critically important factor when casting a sinking line is to keep the line moving once you have brought it up to the surface. Do not pause after the preparatory roll cast or the line will immediately sink below the surface again making an effective spey cast virtually impossible.

Mending the Line

A line cast across a fast current soon develops a downstream ‘belly’, and this causes the fly to be drawn rapidly across the river. To reduce this effect, and so ensure that the fly swims at a greater depth and more slowly across the river, you need to ‘mend’ the line.

Once the line touches down, swing the rod tip in a semi-circular movement up from the surface and then upstream; this will project the belly of the line upstream of the fly, so delaying the time when a downstream belly drags the fly across the river. (When using a floating line, you will be able to mend the line more than once per cast if necessary.)

Shown n the left is the the casting technique for casting an 'air mend'. With practice you can create an upstream mend by means of a gentle side-to-side movement of the rod while the line is still travelling through the air. This is particularly useful when fishing with fast-sinking lines, which are very difficult to mend once they have touched down onto the surface of the river.

A line cast across a fast current soon develops a downstream ‘belly’, and this causes the fly to be drawn rapidly across the river. To reduce this effect, and so ensure that the fly swims at a greater depth and more slowly across the river, you need to ‘mend’ the line.

Once the line touches down, swing the rod tip in a semi-circular movement up from the surface and then upstream; this will project the belly of the line upstream of the fly, so delaying the time when a downstream belly drags the fly across the river.

Backing up

In summer even a major river can shrink to barely a trickle between near-static pools. A fly cast across the river just hangs there, hardly moving, and unlikely ever to attract the attention of a salmon. To impart movement to the fly, walk slowly upstream after each cast so that you create a belly in the line; as the fly travels across the river towards your bank, it swims first downstream and then upstream until finally it comes round onto the ‘dangle’. This effect, commonly referred to as ‘backing up’, can also be achieved to a limited extent merely by swinging the rod tip slowly upstream as the fly comes across the river.

Excited at the prospect of flyfishing? So are we, and we're pretty sure you would find the Winding River Mystery trilogy of action-packed thrillers gripping reading too. Dead Drift, Dead Cert, and Dead End are Pat O'Reilly's latest river-and-flyfishing based novels, and now they are available in ebook format. Full details on our website here...

Buy each book for just £4.96 on Amazon...

Please Help Us: If you have found this information interesting and useful, please consider helping to keep First Nature online by making a small donation towards the web hosting and internet costs.

Any donations over and above the essential running costs will help support the conservation work of Plantlife, the Rivers Trust and charitable botanic gardens - as do author royalties and publisher proceeds from books by Pat and Sue.